Everybody loves a comeback but is Netflix revival built on more hope than potential.

The aim here is to find quality companies with a robust outlook and an economic moat at a cheap price.

Easy.

It’s not like that’s what everyone is looking for….

So, does Netflix make the cut?

Background

Over the past decade prior to 2022, Netflix was a growth stock darling. Massive year-on-year subscriber growth, consistent Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) growth and little competition meant there was no limit to the company’s potential.

But of course, there was.

There is always a limit.

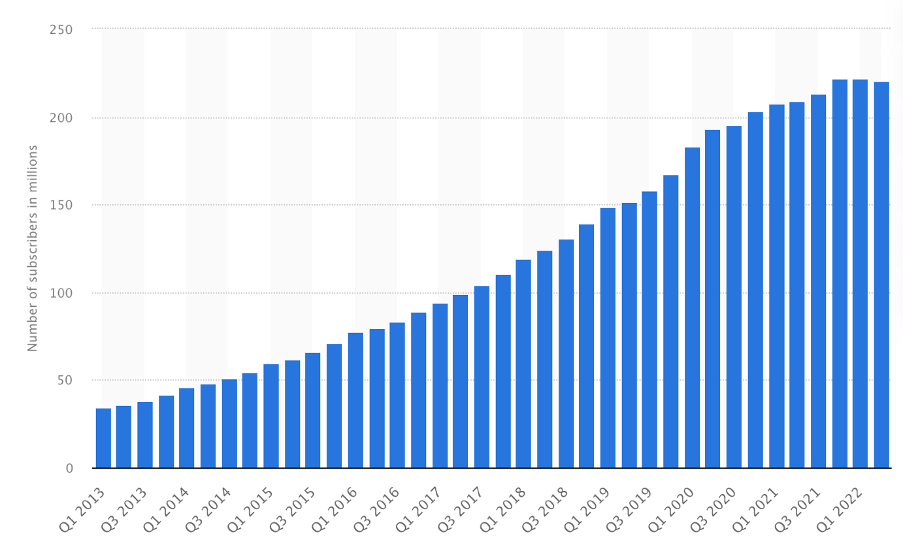

Netflix Quarterly Subscriber Growth

(In Millions)

Source: Statista

As with so many of the growth stock names, once the assumption of constant growth starts to unravel, so too does the stock price.

Netflix was no different.

In recent months, the growth narrative around Netflix has shifted quite dramatically as subscriber growth slowed, stopped, and reversed course. Once this growth narrative changed, so too did the price investors were willing to pay for it.

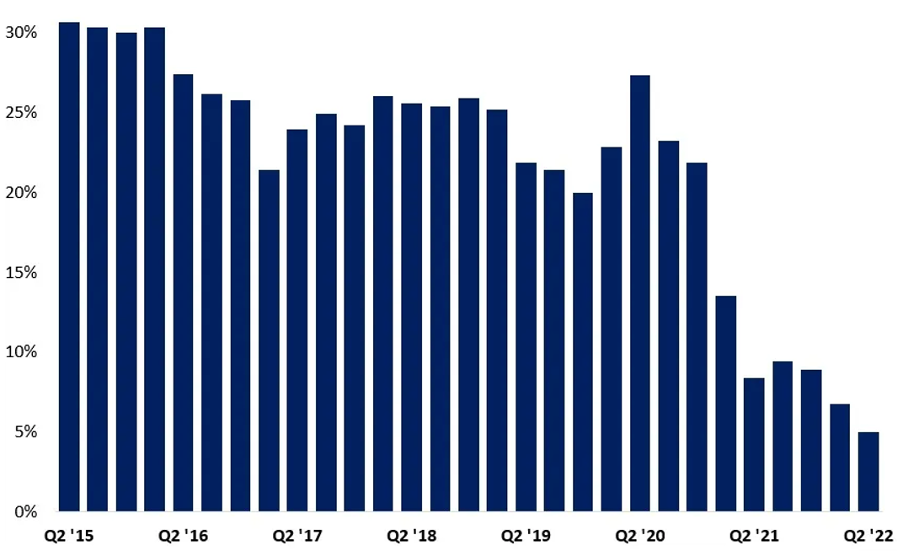

Netflix Year over Year Subscriber Growth

Source: Statista

We see it time and time again, Analyst growth models projecting endless revenue are built upon holding current growth rates constant. But, of course, growth is never constant.

The law of large numbers ensures that growth rates become harder and harder to replicate over time. It’s not that larger companies cannot continue to grow; it’s the rate of growth that gets inhibited.

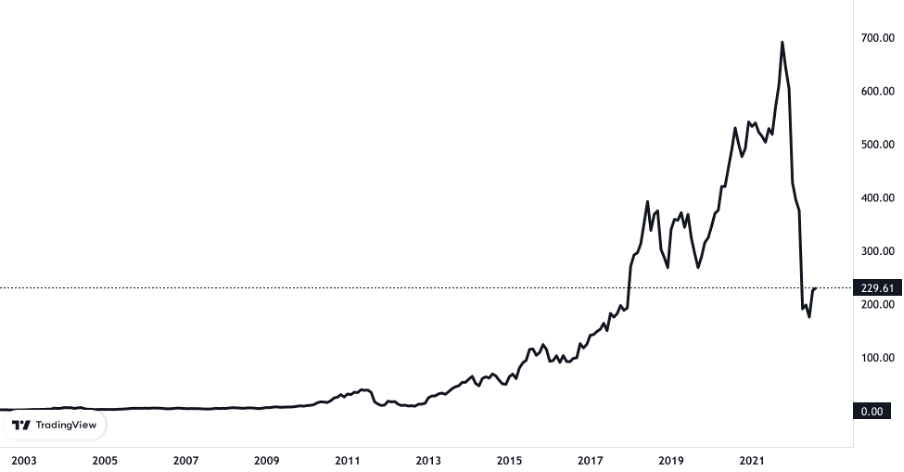

Netflix is currently down over 60% year-to-date.

Despite having five times higher net income, double the revenue and over 100 million extra subscribers, Netflix is now trading below its December 2017 price.

Netflix Stock Price Movement

Source; TradingView

Netflix was a classic case of ‘great company, bad stock’ as too much of the growth story had already been baked into the price, leaving little room for an upside surprise.

Now, as the growth outlook changes, the endless growth narrative that pushed it to record valuations has to be re-examined.

Robust Outlook?

Now you could argue that these lower subscriber numbers are simply a post-pandemic lull given the pull forward in numbers that Netflix experienced in 2020/21, but in my opinion, this is more of a systemic issue.

Unreasonable Expectations

The Total Addressable Market (TAM) is essentially heroin to a growth stock junkie. Said junkie can theoretically argue that Netflix’s TAM is anyone in the world with access to the internet in the same way that Uber argued that its total addressable market represented a $5.7 trillion opportunity in its IPO in 2019.

The incentives for companies to exaggerate the growth opportunity are obvious, but I like to take a more realistic outlook.

There isn’t an endless pool of subscribers for Netflix to dive into; Each customer conversion becomes more difficult from here on out.

Add in the need to simultaneously maintain existing subscriber levels, and Netflix’s subscriber growth outlook becomes a bit more anemic.

Inelastic Price

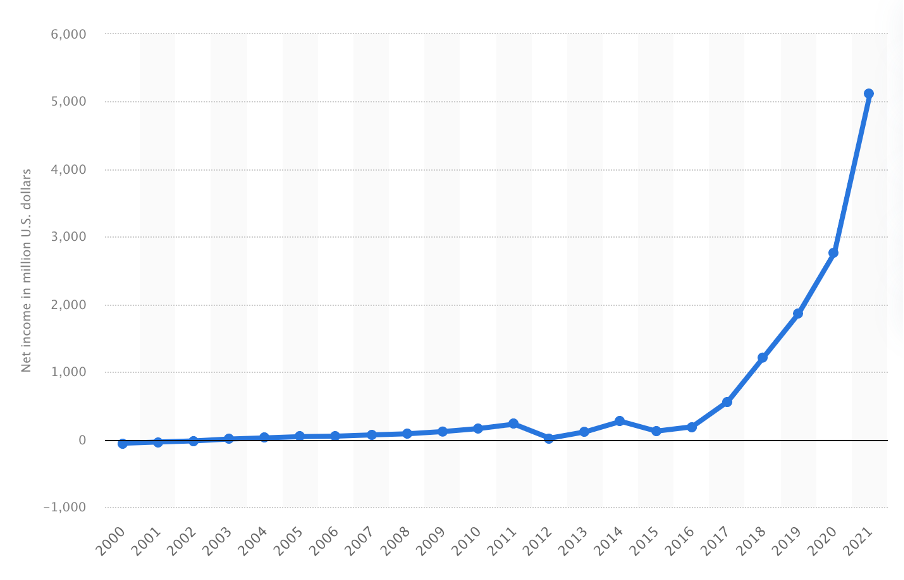

While subscriber growth is important, the bottom line is what matters. Netflix has gradually increased subscription pricing over time, increasing the all-important revenue per subscriber figure and boosting profits in the process.

The considerable increase in their bottom line during 2021 while dolling out a record $17 Billion on content is impressive, to say the least.

Netflix Net Income

(In Millions U.S. Dollar)

Source: Statista

But we can’t assume that Netflix has complete price inelasticity and can continue to pass on price increases to its customers year-on-year.

In 2019, the company managed to generate ~$120 per subscriber. By 2021, this figure had jumped to just under $134, but crucially, these higher prices were met with falling subscriber numbers which suggests that Netflix may be approaching their price ceiling.

Previous price increases were from an initially low-price base as Netflix focused on customer growth over customer revenue, but each incremental price increase will likely be met with growing resistance going forward.

Ad-supported subscription offerings and a continued clampdown on account sharing may help revenue growth, but I’m not convinced this is enough to create the substantial growth they are looking for.

New Approach

Market forces have conspired to push Netflix in a new’ financially responsible’ direction.

For the past decade, investors have had greater tolerance for non-profitable growth companies, but as interest rates rise, free cash flow has become the order of the day.

Slowing revenue growth combined with the market’s likelihood to reward Free Cash Flow heavy businesses going forward has resulted in a shift in focus for Netflix as the higher up’s look to rein in spending.

“We’re now through the most cash-intensive part of that transition. As a result, our cash content spend-to-content amortization expense ratio peaked at 1.6x (along with peak negative FCF of -$3.3B in 2019) and is expected to be about 1.2-1.3x in 2022 and to decline going forward, based on our current plans, which assume no material expansion into new content categories in ’23.”

But in an increasingly crowded industry, can they simply reduce their biggest source of differentiation as a streaming service: fresh original content?

Don’t get me wrong, I can see the attraction from a financial perspective as tidying up margins will likely improve their valuation multiples, but it seems a bit short sighted to me.

A reduction in spending while still leveraging the relatively new back catalogue should lead to more attractive earnings without disturbing the subscriber numbers too much, but the sustainability of lower spending in an insatiable, content-obsessed, ultra-competitive market seems optimistic at best.

Every company wants to reduce spending, but the desire to cut costs is not enough to make it a viable choice.

For me, the new plan to reduce spending ignores the elephant in the room. Whether it likes it or not, Netflix has subjected itself to a life on the ‘content production’ treadmill where the belt never stops, and the only options are run faster or fall flat on your face.

Economic Moat?

You know the marketing department has done their job when the company’s name becomes a verb.

Netflix’s logo is instantaneously recognisable, it has cemented itself in the urban vernacular, and even its “Ta-Dum” intro sound is iconic.

There is no denying that Netflix is the strongest brand in the Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) streaming space and one of the most recognisable brands in the world.

They established this brand appeal by spilling billions of dollars into producing original content and content acquisition. They spent roughly $80 billion creating content from 2014 through 2021. An investment that ultimately paid off as it gave them the global scale necessary to make the DTC streaming service a viable long-term business.

Given this first mover advantage and relentless cash burn, Netflix had generated a significant economic moat. Any media company looking to compete with Netflix would have to be willing to endure significant financial pain just to enter the ring.

Unless, of course, you’re Disney, that is.

With over 100 years of creating content that the world loves under Disney and then Marvel, Pixar, Star Wars and National Geographic and arguably the most widely recognised brand in the world, Disney was always going to be an able competitor.

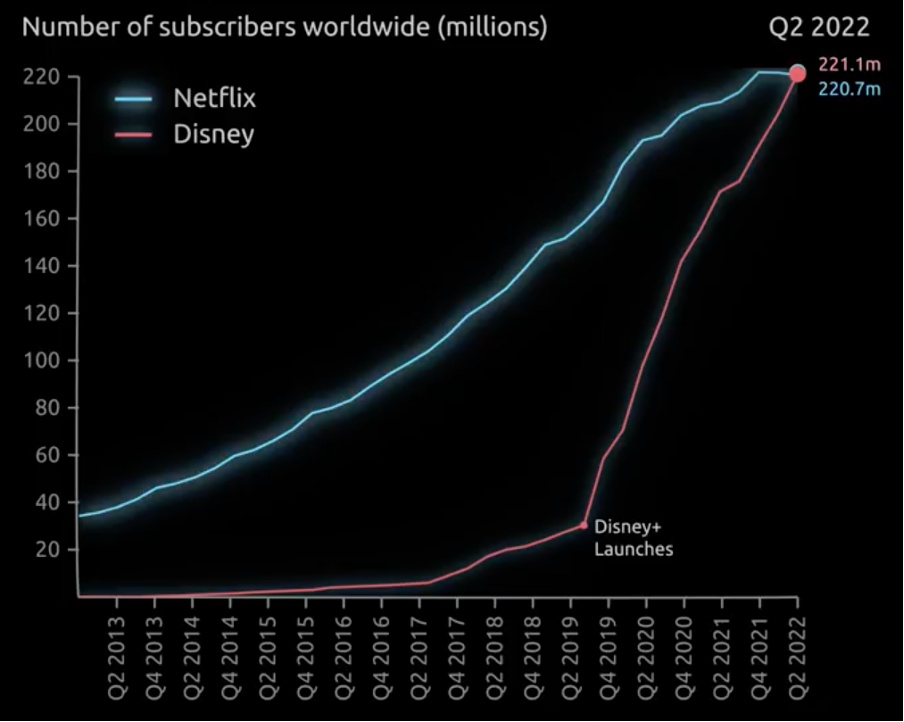

But the speed at which Disney stole market share even surprised Disney themselves. Just two years since its launch, Disney now has more subscribers than Netflix (worth noting that these subscriber numbers include Disney + as well as ESPN+ and Hulu).

Netflix vs Disney Subscriber Growth

Source: James Eagle Data visualiser

Two things worth noting here.

-

- Firstly, the choice between Disney and Netflix doesn’t need to be mutually exclusive.

As we move forward, consumers will hold a bundle of service providers in this space, but there is also an upper limit to how many names a consumer is willing to hold within that bundle.

As such, each new name in the streaming wars is vying for the same piece of the overall pie.

Despite this increased competition, I believe Netflix and Disney will maintain their dominant positions due to their global scale, branding and content strength.

More importantly, they can co-exist in this space without significantly inhibiting the growth potential of the other. The rest of the names, however, may be left fighting for scraps.

-

- Secondly, the subscriber numbers only tell half the story.

The goal isn’t just to maximise the number of subscribers but to maximise the revenues generated from these subscribers.

Disney subscribers are currently paying an average of ~$4.4 per month. To put that number in context, Netflix’s average subscriber (globally) is paying ~$12.0 per month.

So, while the rate of Disney’s subscriber growth has been impressive, Disney is still in the early stages of that journey. I expect that as Disney attempt to increase their price point, they will experience the same growing pains that Netflix has endured in recent quarters.

Crucially, If Disney cannot implement the necessary price increases while maintaining current subscriber levels, then the economic viability of the entire DTC streaming business comes into question.

Cheap Price?

As I mentioned previously, too much of Netflix’s growth story had been baked into the price, leaving little room for an upside surprise.

Now, with the recent sell-off, there appears to be a much more reasonable entry point on the table despite a more modest growth outlook and mounting competition.

Given the brand appeal, planned reduction in spending, extensive back catalogue and first mover advantage that Netflix holds, there is a lot to love at a sub 20x P/E multiple.

And with corporate hell-bent on improving the free cash flow numbers over the coming years, I could quickly get behind the idea of the stock price increasing over the coming quarters.

My Biggest Issue

There is one niggling issue that is stopping me from buying in long term.

Strangely, for someone who likes to run the numbers, my single biggest deterrent is entirely anecdotal.

In short, I’m just not sure how economically viable the DTC streaming business is for one simple reason. The burden of content creation will always reside with Netflix, and our propensity to consume is seemingly endless.

For example, Netflix had a recent win following the success of ‘Stranger Things’ season 4, but it cost over $270 million to produce. While it may have taken Netflix 3 years to make at $30 million an episode, it was undoubtedly consumed by subscribers in a 6-hour binge on a Sunday afternoon while simultaneously scrolling on their phones.

It’s not that Netflix can’t compete with Disney; They can’t compete with our insatiable appetites, and this doesn’t look set to change.

In my opinion, this idea that Netflix will reach a point where they can significantly increase profit margins by reducing their content spend is naïve. The content production wheel can never stop.

Once the content dries up, so too will our consumption and our subscription fees. No amount of extensive back catalogues will make up for a lack of new and original titles.

I believe that Netflix will remain the dominant leader in the space, but the space has a ceiling in terms of how profitable it can be. The margins look set to be perpetually tight.

When compared with business models like YouTube, the content burden that Netflix has tied itself to becomes all too apparent.

YouTube generated quarterly earnings of $7.34 billion vs. Netflix’s $7.97B in Q2 2022 for a fraction of content spend.

Youtube has positioned itself as broadly content agnostic. No endless production teams or movie sets. Instead, they function simply as the infrastructure on which the content sits, paying the creators a marginal fee for the privilege of their network (On average, 100,000 YouTube views are worth around $500).

More specifically, ‘Mr. Beast’ was the highest-grossing creator on YouTube in 2021.

YouTube paid him $54million in return for roughly 5 billion views across his channels.

While there is no direct comparison, as Netflix conveniently show their viewing statistics in ‘minutes viewed’ instead of actual views, it’s fair to assume that Netflix’s price-per-view spend is considerably higher.

In Youtube, Google has created a streaming giant cured of the content creation affliction.

Unfortunately, Netflix is still very much infected, and there is no known cure.

Final Word

From a price and economic moat perspective, there is a lot to like here, and I can easily foresee several ways in which the stock price moves higher over the medium term.

But investing is a relativistic game, and you cannot jump on every opportunity.

While still a great company, the recent transition from growth to maintenance mode combined with its perpetual content burden will result in slower growth with little scope to significantly improve margins. As a result, I believe that the streaming giant’s next decade will be far more challenging than the last.

I will do some swing trading on this one over the coming quarters, but I will pass on any meaningful long-term positions for now.